|

The

Salt Miners |

|

By Domenico CORTESE

(Translation of Alicia Bodily) |

So

many have visited the Salt Mine and several of them have written about it.

Something in particular shares a common thread in all the writings: the

comparison with Dante�s Hell.

Leonardo Alberti,

a Dominican friar, around 1525, described the Salt Mine as follows: �A

mile away from here are the salt mines, Truly it is a marvelous thing to enter

in those long caverns made in the entrails of the very high hill, some of

which continue for half a mile, and some more than one, where they excavate

the salt�.

Melograni, in 1811, on the conditions of the workers: �I also watched uncomfortably as I saw that the daily transportation of the salt inside the mine, is carried out on the backs of adult men and of young men. The former carry on every trip about two hundred pounds of solid pieces held up with a rope; the latter, one hundred pounds of �sterro� (loose pieces) in sacks. It is pitiful to observe this, a procession of naked men carrying out the task of beasts of burden, being careful, as they march in single file, not to be a hindrance one to another by hitting his load against the narrow passages that each must tread, and every one of them, oppressed by the weight, and tired by the suffocating heat of the mine, finishes his day gasping and at their wits� end �.

PICTURESQUE POLIORAMA (1839/40): �It was the dawn of a beautiful August day, as I was coming down from the hills of Altomonte, absorbed by sweet memories. By way of an easy and pleasing slope, I arrived in the company of certain friends to the Mine formerly called of Altomonte, now of Lungro; which thanks to the elaboration, the trade and the transportation of salt, rose from being a poor Albanian hamlet of Altomonte to the state of a respectable town, even to become the main town in the area�I discovered on the space near the entrance of the Salt Mine, called Mandriglio [�Corral�], a multitude of vehicles. I saw a continuous bustling about of many people, a swarming of workers, a coming and going, a perpetual movement; I heard a loud noise, and alternating Italian and Albanian voices. Upon entering with my friends in the lowest pits [referring to Dante�s Hell] under the trembling torchlights, a mixed feeling of curiosity, of pleasure and of terror ran through our souls before such unusual novelty. The scenery before our eyes was a surprising spectacle; hills, valleys, flights of steps, ancient gallery floors, precipitous descents, all made of rock-salt� and while descending those longest stairs I began to recall the verses of Alighieri.

� You will see

clearly

how the bread of another tastes of salt,

and what

a harsh road it is to go up

and down on someone else�s stairs.�.

verses

that were rendering themselves more meaningful in the interior of that

hypogeum, in a sky without stars, in the sight of so many naked individuals

out of breath striking with large picks, cutting down and cleaning rough and

hard boulders, or curved under the weight of large loads that they were

carrying, and opening their way ahead shouting: �vem jast � vem jast� We

are going out, we are going out. They seemed to me like roaming specters in

the kingdom of shadows. The beautiful sapphire of the Italian sky had

disappeared, and the harmonious and sweetest language of the land and the sun

could no longer be heard. Instead we could hear words and accents of another

language, and the shaking of the mountain thundered in our ears, while the

crunch of the rocky crags, from which enormous salt stones were being pulled

out, and their thundering while falling down, mixed with the harsh and rough

accord of the repeating blows of the laborers�.

Giuseppe Samengo reports thus: �...

Plunging down as on the side of a mountain on a set of dreadfully

built steps now falling apart, one descends to the gallery called Lower Pit;

which is a true example of Dante�s Hell, such as this is partly an example

of the physical and moral world...

Here an uninterrupted series of deserted, abandoned galleries,

which are wrapped in unending darkness, and piled up one above the other as

far as the eye can reach up; there a drossy chaos of salt of every shape, of

every size thrown around on top of the most bizarre and majestic mess; further

away a most spacious threshing-floor all decorated like a theater on a festive

day; and arches and fencing and pyramids and columns and walls carved by

chisel, on which, as in a solar prism are fragmented in thousands and

different colors the pulsating rays of the lights hanging in every path and

nook of the large Mine; and all of this immense and confused heap of walls, of

ceilings, of spirals, of paths stowed, scattered and set up above like huge

wings attached to the body of an enormous bird; and all of this irregular

basin furrowed again and again in all ways and means into compartments,

threads, triangles, scribbles; and through these paths here and there, and

through these hampered areas, Employees, Managers and Foremans who meet one

another and bump onto one another at all times opening and bringing together a

mixed up multitude of men, of youngsters, of old and young workers who, like a

stormy high sea broken against innumerable rocks now comes, now goes, now runs

along, now stagnates, and always froths up and gurgles; and the rolling of the

stones that fall along the edge of the precipices, the banging of the hammers

of the workers, the swarming of the operators, the lamentations of the wounded,

the rustlings of the footsteps, the rebounds of the pavement, the thundering

of the underground, and all of these voices and all of these frequent sounds,

noisy, animated, shudder and oscillate around you like an only scream, long,

sustained, continuous��

De Marchis states: �To him who during the studies

of early youth pleased to immerse himself in the readings of the Most High

Ghibelline, and enjoyed himself with the beautiful images that embellish the

landscape of the triple kingdom, those cavernous pits represent an interesting

scene, which serves to prompt to his memory those immense compartments, that

the Poet with uncontrollable fantasy imagines as a part of hell �Watch those

hundreds of naked workers, intent on cutting the Salt in the various areas of

the Galleries, under the feeble light of a few lamps, that multiply the

shadows projected on the white rocks, and confess whether or not the

shuddering imagination does not hurl you out into the great concentric circles,

seats of pain, and of eternal desperation? �

Padula states: �The gallery called Lower Pit

reminds the individual of Dante�s Hell. Precipices suspended above his head,

precipices opened under his feet, enormous masses of pack saddles that

threaten harm. Here deserted, dark galleries, one above another, there a

threshing floor like a theater hall with arches and pyramids, and carved walls,

which reflect the light of the lamps hanging in every corner; and through

those labyrinths, men and youngsters;

and rocks that tumble down, and hammer blows; and thundering of the

undergrounds�

What a pitiful scene! The salt is taken outside on the backs of men

and youngsters. The former take on every trip two hundred pound blocks held up

with ropes. The second bring along one hundred pounds of powder inside the

sacks. Those people, who arrive at the open air out of breath, move one to

compassion. In the mine in some places there is water; ventilation is lacking�

The mine has the misfortune of not having been developed

horizontally, but it was excavated down through labyrinths. It is enough to

say that there are some stairs on a near vertical incline�.

Tajani: �By sheer continuous dedication

to the harsh labor of mining came about the monetary resources not enjoyed by

others and perhaps also envied. But what sweat have those earnings not caused?

What hardships did the miners not have to endure? What toils did

they not have to bear? The exploitation of the mine was made increasingly

difficult as it became deeper, the desire for earnings forced people to

overcome many inconveniences, but side by side with that which was useful,

ahead of need was also an inadvertent and contemptuous evil which was the

physical deterioration of a population, procured by those who should have

looked over their well being, and over their prosperity. Neither has that

condition changed much in our days, because out of the improvement works that

were implemented several times, more or less effective in achieving the triple

goal of increasing production, facilitating the bringing up of the product to

the light of day, and mitigating the harshness of the work, it has always

remained true that trying to substitute raw labor with machines was always

blocked by the usual prejudices of the masses. Deluded by an insensible

philosophy, and by the fear of seeing lowering employment, that font of

prosperity has continued to be the cause of attraction and of physical

degradation. To permit men to make a living by submitting themselves to

transport material loaded on their backs like beasts of burden is unacceptable

tolerance on the part of any government. If such a disgrace of humankind could

have been at one time compensated by job security, now perpetuating that harsh

work would have been an undignified action on the part of any government. A

modification therefore was introduced in the method of excavation and

transportation, although it was something really small, because the

exploitation of mountain salt in Italy suffers great competition from sea salt,

and the salt industry will have to function one day within a system of free

production. But until then a monopoly must exist. Be it in the hands of the

government, be it in private hands, consideration for the working class always

must exist: It is a matter of civil progress, thorny for governments and for

economists�.

Bellavite: ��.

But also to improve the conditions of the porters, who naked and gasping,

climbing on the inclined surfaces and going through large caverns, had to

carry on their backs the excavated material, reminding the observer of the

damned of Dante� �.

The

geologist Torquato Taramelli: � Most

of them, untiring and patient as ants, go up and down those fifteen hundred

steps in a double current, naked, breathless, panting; and they carry on their

backs at least forty kilograms of salt. Others, with great skill, profiting

from a certain great slope of the rock, throw down great parallelograms that

fall with a great noise on the floor of the ample excavated rooms, break apart

in smaller pieces, and provide labor for the category of the sifters.

The less pure material, which however always contains at least four fifths of

salt, is thrown on piles and taken from a rivulet near the mouth of the mine.

At the end of a well I saw a winch, but it wasn�t working. Transporting salt

on backs is more economical, and those people earn no more than one lira per

day�.

As can be gathered from reading the descriptions of these visitors to

the Salt Mine, the working conditions were inhumane, even considering that, as

Sole writes, �the rule that prevailed, at the request of the

workers, was to alternate workers in the hardest tasks, and to show

|

|

|

regard for the older workers, who after having toiled for many

years, were utilized in the distribution sector. Furthermore, in the mine

there was not a single mechanical instrument to render the work of the

laborers less taxing and the �descent� was incredible, if one thinks that

the miners had to walk down hundreds and hundreds of steps to arrive at the

active sites and then go up several times a day with sacks full of salt. The

cutters, armed with picks, wedges and punches, cut the salt from the walls at

an infernal pace, given that their pay was established according to the

quantity of salt that they were able to cut out. The workers picked up the

salt and the �pack saddle� and proceeded to take it to the three deposits:

Ammendoletta, the New

Gallery and Providence. The workers were able to transport the salt, which

later was weighed. The masters, instead, were in practice builders and

carpenters and proceeded to raise the sustaining walls and the steps and

they managed to build anything that was necessary for the mine. The loaders

were practical in placing the sacks of salt on the backs of the carriers, the

lamp lighters provided the illumination of the mine and the gatherers raked

the finer pieces of salt that remained at the sites�.

|

|

The

inhuman working conditions prompted the workers to protest in order to

preserve their health and their interests. A spirit of cooperation and

liberality developed among the workers. In fact they founded the Association

of the �Salt Workers� with the purpose of assisting the workers who

because of health or for other reasons needed help. Saint Leonard was a Member

of the Association, their protector, whose presence was acknowledged every

morning, along with the daily pay. The first to be called for the collection

of the stipend was Saint Leonard himself.

Padula, who was the most acute observer about

the conditions and the character of the populations of the province, writes

about the salt workers of Lungro: �At the mine they work 8 hours; but

because for every kind and for every worker the time that he is to work is

determined, the majority are done after

2 or 4 hours of work, and they go home. The miners tell each other how their

wives cheat on them, their own swindles and defects, without quarreling about

them. They tell their superiors their thoughts with great passion. They are

extremely resentful, biting and mordacious. They love excesses, they aren�t

careful with their money, and after they are paid every two weeks, they don�t

hesitate to pay their debts and to celebrate at the bars. They are all

liberals�.

In

1842 was instituted a �Savings Bank� for the workers, set up to assist in

case of illness or disability. The association lasted till 1884.

Padula states:�

Since 1842, with the great

Francesco Fava called as the director, the salt miners set up a savings bank

in order to get assistance in case of illness or disability, which collected

every end of the month 300 ducats�.

In

Lungro, in opposition to the rest of the area, the presence of industrial

activity that employed a consistent number of workers gave birth to a spirit

of �union�. Indeed in

Calabria in the mid 1800�s the feudal system was still in place. Francesco

De Santis, who sought refuge in Calabria in 1849 to run away to the

persecution of the royal police, in a lecture given in 1873 about the

Calabrian culture which took place at the University of Napoli, described the

environment this way: �In Calabria the environment still smacks of feudalism. I was there

because I was running away to avoid an order of arrest and when I arrived I

told myself: -Feudalism here is still in force��

It

is important to consider the contribution given by the salt miners in the

fighting for the unification of Italy. While in the rest of the country the

political secret societies of the Carbonari was the expression of the

bourgeoisie and of the higher social classes first, and of the middle and

small bourgeoisie during the years of Young Italy, in Lungro, side by

side in the political struggle, we find intellectuals and workers. In the

movements of 1848 �nearly two hundred men, with their hats or their

chests adorned by the tricolor cockade, during the first days of June,

commanded by Domenico Damis, took

the road for Campotenese to defend the proclaimed constitutional freedom in

Calabria,��(Let�s talk about Lungro � 1963). Among these,

there was a high number of �proletarians�.

Indeed among the arrested and condemned, beside the pharmacist or the

commander, we find the salt miner, the shoemaker, the tailor and the farm

owner.

Of

the five hundred men of Lungro gathered under the flag of Garibaldi in 1860 to

combat against the Bourbons and for the Unity of Italy, most of them were salt

miners.

�

The liberation, for which they fought strenuously, as has been noted,�

-writes G. Sole- � did not free the salt miners or improved their inhuman

working conditions; instead, for some, the situation grew worse under the

direction of the new directors who came from Piedmont.�

In

this period (1845-1860) there were discussions about the true usefulness of

working in the Mine as part of the economy of the town.

Rodot�, already in 1763, wrote: �The caves of salt, great work of

Nature, are of much usefulness for the citizens, who from its sales earn a

considerable amount, and introduce in the town a lot of products from outside.

For all of this they consider that this Town is the capital of the [Italo]

Albanian nation�

Picturesque

Poliorama (1839/40):

�The said Salt Mine has a lot of advantages. It employs a lot of manpower

that without this resource would have been rendered useless, and perhaps

detrimental: It has diminished, and it will continue to take away from the

rough bark mountain habits of the neighboring populations, it has thrown noble

seeds of honest speculations,��

Padula :� There are 670 workers

there, and they are, and they earn, being different in

class, according to age - 120 salt cutters: grana 23 for every time

they weigh in: 290 workers, according to age, per day, grana 22 -17, 12 -9, 50

chippers: grana 22 per day; carriers: 30, 25, 20 per day, according to age;

masters: idem; 90 lamp lighters, porters, chip gatherers: 22, 17, 12 according...;

39 assistant managers: grana 40, 30, 20 (a shameful thing)�The directorship

of the mine is made up of: A director with a monthly salary of ducats 543; a

supervisor with 36; an accountant with 14; an archivist with 14; an engineer

with 36; a clerk with 18; a second clerk with 16; a third clerk with 12; head

security with 13 and grana 40; 5 weighers, and each has 15 and grana 40; the

foreman, who distributes the work, 20, 40. Besides this there are those who

guard the salt mine: 21 national guards, 8 customs guards, a brigadier and an

under brigadier, who as a group get 4,300 ducats per month".

Giuseppe Samengo: �It

has been said that Lungro is indebted to this establishment for its wealth and

for its leadership over all the Albanian villages, and I don�t deny it. But

I also say that agriculture, that at other times forced this land to bring

forth its treasures, now languishes, precisely because the townsman,

seduced by the eventual and momentary advantages of mining throws away

on the fields the implements of his trade, and picking up a huge pick axe

abandons that land that never merited the name of step mother to go into the

horrors of these innermost recesses. Commerce, to tell the truth, at least regarding the

topographical location of the town, is in a most flourishing state, as

attested by the presence of its numerous merchants: who, without having any

money, set up early on the public streets a kind of shelter or hovel, where

they give away fibs, good food, and exquisite sippings to those who come by,

and pick up a little bit of earnings: then with coins turning into more coins

they get to fill a store with merchandise and you see them day by day getting

in better and better shape.�

Samengo,

although admitting the benefits that the town receives from the Salt Mine,

regrets the diminished availability of manpower dedicated to agriculture.

An

interesting response to Samengo�s concerns, which we transcribe wholly, was

given by De Marchis: �The

French Government, which overturning all of our institutions with heavy hand,

in order to substitute them with new ones, looks like the person who patches

up a new building with the falling ruins of an old one, was preparing another

administrative plan around the salt mine. It put up a separate directing

organization represented by a Director, a Supervisor, two Clerks, several

Weighers, an Engineer, the Guard at the door, and a Customs guard established

under the command of a lieutenant in charge not only of the surveillance of

the Mine; but also of suppressing Contraband

�It was established by a financing organism, that the merchandise should be

transported to the warehouses of the monopoly that were opened in several

localities in the province, and there under the care and responsibility of the

Receivers elected by the King ,it was taken out to the Towns, to privileged

vendors with expenses being charged to the royal coffers.

This new system organized under other views of public economy was put into effect, and it contributed not a little to improve the conditions of the town; because Lungro enjoyed since that time the benefit of 3rd class direction; of a royal warehouse in the monopoly, and by being appointed as a Head of the area, it has been obligated to receive in its midst a large number of employees from outside, who were instrumental in civilizing our ancient customs.

And I feel that I have the obligation to submit to a brief examination the opinion of those who, instead of thanking the eternal providence for having given us the gift of the mine, without which Lungro, instead of having a prosperous progression would have remained in the primitive condition of obscure Hamlet, continue to sustain that the mine brought about evil, instead of good to the Town, because it took the inhabitants away from Agriculture, profitable source of every true and real comfort.

The salt mine due to reimbursements from the government approximately doubles the yearly income. Twenty two thousand, which sum is given away completely to the town, like a beneficial dew directed to the relief of the population, and the employees themselves spend their money for personal needs, as well as for home rents, and other luxury items. Add to all that the arrival of the vehicle drivers, and couriers, who without interruption must get here, in order to transport the salt to the several warehouses, and deposits, circumstance that gives a gallant impulse to the commercial industry of the locals, to provide the town of all that is necessary, and providing that the cash doesn�t leave their hands, realize the effect of equality of comfort for all of them.

On the other hand, Lungro owned in times past a narrow territory which was not enough to offer all means necessary to live without assistance, and with the division of the public domain, it was able to extend the patrimony of the Town; even so the lands acquired are located mainly in the center of the mountains which are inaccessible in winter because of the snows that cover the surface, and which don�t lend themselves to all the improvements that are required by sensible agricultural practices. In spite of this, while the introduction of less hardy trees has not been successful, and only pines, turkey oaks, and beeches grow well, it is not impossible to take advantage of a limited harvest of grain, rye, and potatoes, the same as of summer pastures that bring about the advantages of additional lands for herding.

On the other side, in the easternmost locations grow well grapes, olives and mulberries, and the harvest of their products brings to the owner fairly good resources, to help him live in comfortable conditions. Agriculture therefore is not neglected, as it is wrongly expressed, and if it isn�t for the town a primary means of public utility, the defect lies in the narrowness of the territory, in the rigid climate, and in the not very fertile quality of the land.

Now if the salt mine had not

existed, or if it had exhausted its treasures, and if the citizens had been

constrained to occupy themselves with cultivating their lands, the Town, far

from going through the progressive outburst in which it finds itself, would

cry undoubtedly in misery, and good proofs of this fact are to us the

surrounding towns, which have either stationary or else declining populations,

in spite of the extensive, and fertile territory they own, and with citizens

that are almost entirely dedicated to agriculture.

In them the abundant harvests

fall into the hands of few owners, and the general population is always needy,

and doesn�t live as comfortably as it should, because no other secondary resource is present to mitigate the squalid

darkness.

It isn�t therefore the wealth restricted in possession of a few, but its useful spreading in general, that animates, and reinforces the increased income of the inhabitants, and I foresee from now on, that if the salt mine continues to render to the Royal Treasury the actual product, and if the government persists in the exploitation of the mineral, and follows through with the work carried out in the Cunicolo, about which I have spoken, Lungro in the course of fifty years will have a population increase that will bring about the surprise and admiration of the whole Province.�

In 1880 the salt miners began, for the first time, to fight to ask for a salary increase, and an increase in the porter section. �The fight had a positive outcome: The government agreed to increase their salary and to hire a notable number of additional workers� writes G. Sole.

In 1901 they formed the �Salt Mine Operators Society of Mutual Assistance�. The society managed also a store and it was among the most important in the province.

In 1903 they went to the local square to defend a fellow worker who had been dismissed. Thanks to their fight they succeeded in the reinstatement of the worker and in causing the management of the salt mine to step down. �And it is, rare indeed for the time, and not only in Calabria, - writes Daneo in 1981 � a successful strike, carried out above all with �modern� methods and fighting procedures�. Among the accused was also doctor Nicola Irianni, mayor of the town and provincial counselor, that attended to his work near the Mine, guilty of not assisting the sick with care, of agreeing to allow sick leave only to those whom he protected, and of blackmailing the workers that needed his care. The request came to dismiss the doctor. It wasn�t an easy matter because the doctor, by all possible means, tried to divide the workers� front. In 1904 he founded, in opposition to the society of the salt miners, the �Skanderbeg Society of Mutual Assistance� to which subscribed also some salt miners who first had given him a vote of no confidence.

|

|

|

Medal coined by the Society

This situation went on for a while and it was not resolved because of political protectionism.

In

the meantime the working conditions inside the salt mine remained prohibitive

in spite of the fact that some improvements, such as ventilation of the mine,

better lighting in the work areas, installation of a rail with carts to

transport the salt, and where possible, the use of explosives to extract it. The pick was still used and

the rest of the operation was carried out manually.

Through the course of the centuries, as can be seen, there were few improvements made. Therefore, the method of labor was the same in the 1800�s as well as when the salt mine was closed.

The

salt miners saw the fruit of their sacrifices particularly after the fall of

fascism through their children. Few

of those children did not continue their studies. Lungro,

in fact, boasted, in the 70�s - 80�s, of a much greater number of

graduates than those of other towns in the area.

The salt miners, we can say in conclusion, have had a most important role not only for the economic and social growth of Lungro, but also for its cultural growth.

|

|

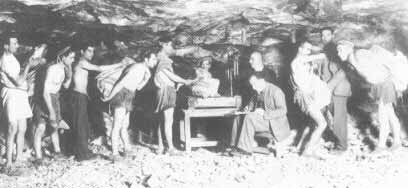

Photo early 1900�s

BIBLIOGRAHY

|

Giovanni

BELLAVITE: |

Cenni sulla miniera di salgemma di

Lungro � Roma 1894 |

|

Agostino

BULGARELLA: |

Osservazioni sul progetto di legge

relativo alla cessione delle saline di Barletta e Lungro � Torino 1862 |

|

Domenico

DE MARCHIS: |

Breve cenno monografico-storico del

Comune di Lungro- Napoli 1858 |

|

Ottone

FODER�: |

Infortunio nella Miniera di Lungro �

1879 |

|

O.

FODER� � L. TOSO |

Relazione sulla Miniera di Lungro -1866 |

|

Giuseppe

MELOGRANI: |

Descrizione delle Saline della Calabria

� Napoli 1822 |

|

Vincenzo

PADULA: |

Calabria prima e dopo l�unit� �

Bari 1977 |

|

Pietro

Pompilio Rodot� |

Del rito greco in Italia � Roma 1763 |

|

Giuseppe

SAMENGO: |

La real Salina di Lungro � � Il

Calabrese� -Cosenza 30.06.1845 |

|

Giovanni

SOLE: |

Breve storia della Reale Salina di

Lungro - Ed. Brenner Cosenza � 1981 |

|

Torquato

TARAMELLI: |

Sul deposito di salgemma

di Lungro nella Calabria Citeriore � 1879 |

|

Francesco

TAJANI: |

Historie albanesi - Salerno 1866 |

LUNGRO

- October

2001